It’s a cold December day, 2016, and I’m trudging back from dropping my son at school; making my ritual return journey through Arnos Vale down the hill towards my home. More recently this has taken a bit longer than usual as I’m looking for seasonal changes in the Ash tree cycle, taking photos and gathering scattered Ash keys along the way. I’ve already collected leaves, buds and flowers throughout the year so this completes my collection.

I’m using these fallen specimens to create a series of projections using an old-school OHP projector, which I picked up from a charity shop. I place a piece of card on the glass which has a large circle cut in it’s centre to allow the light to pass through and I begin to arrange the keys so that they create a border of key-shaped silhouettes around the inside-edge of the circle. I flick the switch and to my joy the projected light creates an impressive design on the opposite wall. I play with the key shapes until I’m happy, change into a long dress (I’ve painstakingly made for a later installation) and climb onto a stool so that my shadow falls in the centre of the halo of light. I start to play with movement while taking images to complete the documentation of the process.

I have decided to experiment with these ideas for a short film as part of a 6 month community project three of us as artists are working on – culminating in two community woodland performances – these projection experiments kick off the process. The performance will celebrate the value, myth and uses of the Ash over the centuries and weave this with the science behind its demise (as the tree becomes increasingly threatened by the Ash Dieback disease).

What I am particularly interested in as I experiment with the projections is the life-cycle of the tree – not just because it is beautiful and fascinating but because this tree stands at the centre of the Nordic creation story – Yggdrasil

I’m interested in drawing from stories, theories and myths like this, which map out cycles of life and shine a light on stages of transition. This interest began at a point of change in my own life when I had to deal with a deep loss bringing with it a significant and sudden change of location, lifestyle and new community. Suspended in a mode of grief I spent years feeling rootless – the loss becoming a strange but alienating comfort as it still linked me to the past. On the face of it I was fine, meeting new people, working, supporting my kids with the transition but in truth I was stuck.

Sometimes what seems like a fairly insignificant meeting actually resets the course you are heading on – I met a group of artists, at this time, on the streets of the local market town demonstrating how to make paint from earth pigments, which they’d dug up along the local coastline. There was something about the idea of digging up these raw, organic materials that tapped into something innate and authentic within me…an urge to connect with the earth. Taking the map coordinates they kindly gave me, I set off a few days later to locate and dig up the pigments for myself.

The act of clambering up across the craggy cliff line and down onto the beach, finding the seam of exposed pigment and scraping it lump by lump from its secret seam made me feel more alive than I had felt for a long time. The pigment I’d chosen to find first was Bideford Black – a sticky black substance, which now covered my hands and marked my clothes. I can honestly say this was a transformative moment in my life. This wasn’t just a foraging trip – it felt like an intentional performance, a passage that enabled me to step entirely into my grief in some sort of partnership with the natural world. The hidden layer of dark matter was evidence of the journey of the earth – a huge and very lengthy transition from Jurassic era to present day. This blacker-than-black pigment emerging through the cliff-face somehow spoke to me about my own hidden grief and its need to be unearthed.

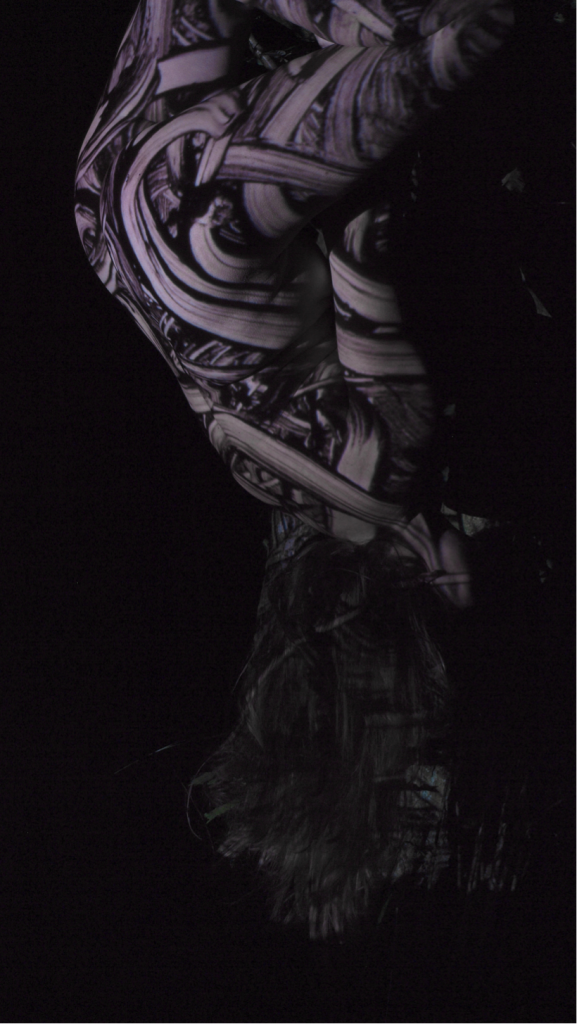

As I began to experiment with making the pigment into paint at home; pounding it down, removing debris, refining it and mixing it with a medium; I knew that whatever I eventually did with this paint would need to be part of a physical process not just painting on canvas. It would be a way of marking the inner shift I was making and bringing the moment out into the world. I created instinctual patterns with the paint and took images of these in order to project them onto my body. It was a brave but necessary response to the need I had to mark my grief. With the help of a photographer friend we captured the powerful images of the black patterns as they fell onto my skin and following the contours and gestures of my body. It was a profound process that was unlike anything I’d experienced before. The synergy with the journey of the natural world – it’s longevity, it’s deep knowledge of change allowed me to safely connect with myself in a way that counselling never quite had.

Since this experience I have read extensively on the subject of transition including areas of depth psychology and deep ecology. It’s helped me to understand why I had felt the need to work through this transition in such a physical way that connects my body to myth and the life-cycles of the land (I have since had similar experiences in water). This has led me to develop, High Noon, an art processes for others who are facing significant transitions including taking small groups into private woodlands for 12 hours to mark their own encounters with grief; processes that enable them to move through grief…not forgetting the loss but acknowledging it’s place in the journey beyond.

When we get stuck in any part of the cycle of life we’re holding on to a permanence that can’t be sustained. The cycles of natural world, of life, teach me that growth and grief are both necessary – in fact it is the ability to embrace the constant of change that makes us fully alive. It enables me to navigate life differently – on a personal level, as a community and even into the huge shifts of a pandemic, climate change and beyond. This is why I choose to work with impermanence.

From collecting Ash keys to digging up earth pigments I continue to work with impermanent processes rather than creating permanent pieces of art – the use of natural materials that get left behind, the dialoguing with others, the projections in wild and urban spaces; this is the art and this art draws people in (sometimes alone and sometimes with others). When that moment ends we are left with the memories, sometimes images and, of course, the changes embraced in the process.

For further reading on embracing change –